In 2018, I was invited to give a paper on my work at the Modernism for the Future conference in Kaunas, Lithuania. I am embarrassed to say I had never heard of Kaunas until that time, but when I visited the city, my jaw dropped to the floor when I saw how beautiful an architectural wonder it was. I would have described the city as Art Deco - a western centric terminology - but they called it "Interwar Modernism", associated with the period of this architectural phenomenon.

The invitation had come from the curatorial programmers of the upcoming Kaunas 2022 European Capital of Culture. Director Virginija Vitkienė, curator Viltė Migonytė-Petrulienė, and architectural historian Vaidas Petrulis expressed to me how they hoped to commission artists to interpret the architectural heritage of the city, its hidden histories, and were aspirational about a UNESCO World Heritage bid.

For those of you who are unaware of Lithuanian history, bear with my speed-dating introduction: Kaunas served as Lithuania's capital from 1919 to 1939. Following the fall of the Romanov Empire in 1918, Lithuania was established without its capital, Vilnius. In just two decades, Kaunas transformed from a small town into a vibrant European Capital complete with civic works, funicular railways, schools, and a bustling cultural scene. Known as the "Petit Paris" of the East, it thrived as a multicultural metropolis, attracting jazz bands from New York, gender bending artists and fostering a rich artistic community.

However, this flourishing came to a halt with the Nazi invasion in 1939, leading to the tragic extermination of the city's Jewish population, many of whom were architects, merchants, and artists who authored this remarkable cultural renaissance. The subsequent Soviet occupation further suppressed Lithuanian identity, erasing cultural expressions deemed threatening to the regime. Censorship was rife and the consequences of speaking out were severe until it got its independence and sovereignty back again in 1990.

When Lithuania began its ideological reinvention by joining the EU in 2003, it turned its gaze westward, embracing neoliberal values. Unfortunately, many of the architectural treasures from the interwar period faced demolition or neglect. By the time I was invited to participate in the "Modernism for the Future" project, many of these buildings were at risk. The curators emphasised the urgency of rekindling the citizens' love for their city before it was lost forever.

I initially had severe reservations about creating a work about Lithuanian culture; it felt ethically unsound to narrate a heritage that was not my own. The curatorial team of Kaunas 2022 tasked me with creating an art film that would reflect the city’s complex history. The citizens of Kaunas have had a complicated relationship with their architectural heritage. The project was fraught with potential emotional and psychological post-colonial landmines, so it was key to involve citizens from this culture in a co-authorship role. I firmly believed that genuine engagement with local artists and residents was essential for the project’s success.

Never underestimate the power of art and creativity to move mountains.

Collaborating with Sandra Bernotaitė, a talented writer based in Kaunas, was key to bridging this moral and ethical conundrum. We reached out to amateur writers to share stories about the architecture from the perspective of the buildings themselves. This collaboration yielded over fifty short stories, revealing untold, imagined, or forgotten histories of the multidimensional multicultural individuals who once inhabited these modernist structures, as well as the suppressed narratives of the city. I was asked to consider how I could work with some of the citizens to help them fall in love again with their architectural heritage and perhaps plant a seed towards saving some of the endangered civic and private buildings.

I used a number of MacGuffins with the construction of this film project, there is not one interpretation of Kaunas but many and the city is never truly revealed in its whole. We used the stories from the volunteer writers to construct the screenplay, drawing inspiration from Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities, employing a narrative structure that mirrors a journey through layered stories.

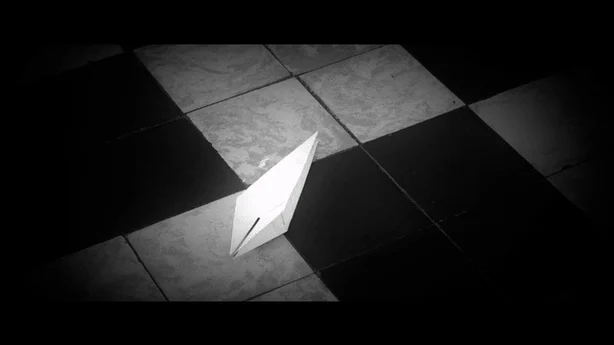

Each short story is spliced into another, and you are taken on a journey through the creases in the walls, the folds in the fabric, down a drainpipe or through a cup and saucer to each manifested world. The film is non-verbal deliberately. I worked with three composers (one of them, Ieva Raubytė, was only eighteen years of age) and the award-winning foley artist Dominyka Adomaitytė, who crafted the sounds of movement and interaction with the architecture. The only voice is the architecture itself, told through carefully crafted sound-scores by fellow composers Arūnas Periokas & Patris Židelevičius. Each sound of the surface was added by meticulous foley, created by my Lithuanian foley artist Dominyka in Jan Švanmajer’s Sound Foley Studio, Sound Square in Prague. Another fitting tribute to my journey to becoming an artist through the support of one of my heroes.

The title "Folds", or "Pleats" as it translates from the Lithuanian, is a nod to the way time bends, history folds and indeed the way visual fictions of stop-motion animation are made. It also spoke to the way the histories of the experiences of the people that lived and worked in these buildings were held within the architecture, like a pleat in the material, only a tiny glimpse is revealed through the movement of this moving image fabric.

I recognise that visual art can often feel like a foreign language to the public, and I strive to engage and empower them in the co-creation of art.

Another key aspect of trying to make this film was to democratise the access to visual culture-making to the citizens. Initially, I had to flee Kaunas because we were all hit by the Covid pandemic in March 2020, right when I had begun filming. I instantly had to switch to teaching stop-motion animation from in-person sessions to conducting animation workshops via Zoom. This was strategically to engage with the city's youth, encouraging them to envision creative and performative ways to embody their architecture. I conducted numerous stop-motion and experimental performance workshops; however, when the pandemic struck, I had to adapt my approach, directing films from my home in Tipperary.

The children’s creations, including wearable costumes inspired by the architecture, ultimately influenced the costumes worn by the Aura dance company during the opening of the European Capital of Culture, reaching an audience of over 2.7 million people - the project grew endless tendrils of influence.

As I reflect on my artistic practice, I often ponder who my work serves and the responsibilities I hold regarding the source material. I am particularly interested in how methodology and context can shape a project, offering a different experience of visual culture. I recognise that visual art can often feel like a foreign language to the public, and I strive to engage and empower them in the co-creation of art. My upbringing in a working-class community informs my commitment to accessibility in art; historically, my community has been underrepresented in the arts.

My own exposure to visual art came through popular culture—television, radio, and public spaces. It is crucial for me that my work is accessible through everyday experiences, so in a research workshop I asked participants about a beloved television show that united all social classes in Lithuania. They unanimously identified The Great British Bake Off. Inspired, I collaborated with apprentice bakers to create edible modernist cakes based on the student bakers’ favourite buildings.

One of these cakes, inspired by the Čiurlionis Museum, even made it into the Guinness Book of Records for the largest Modernist Cake category and the cakes themselves became a kind of strange spin off Icon of the project even though they were designed as props initially for a central reoccurring scene in the film.

I never anticipated the success of Klostės. Initially we were hoping to get one hundred people involved as volunteers, but in the end the film was primarily made through an army of near a thousand artists and citizens who gave of their time freely. They are some of the actors, crew, extras, prop makers and makeup artists what helped sow this moving image fabric together, and I have no idea how we would have done it without them.

In 2023, The Kaunas 2022 team put forward the city to UNESCO to consider its application for listing, Klostės was screened as a part of that bid and the city was awarded World Heritage Status. I could not be prouder to say my work and the people who contributed to making the film happen played a small but significant part in that proposal. In the same year, the film joined our National Collection at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, and it will be screened as a part of that programme in 2025.

It has been one of the privileges of my life to work on an artwork like this. Never underestimate the power of art and creativity to move mountains.

Find out more about the Klostės (Folds) project here.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.