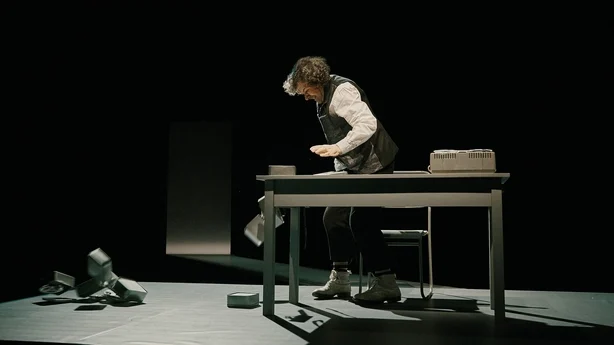

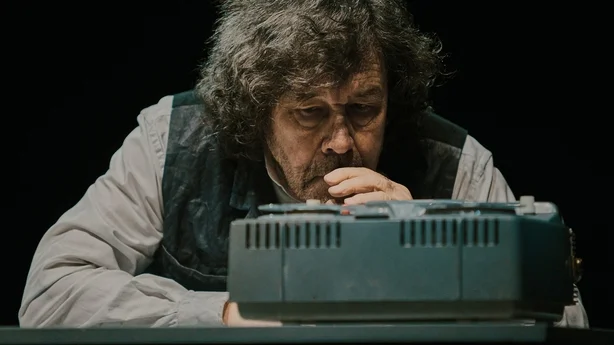

Ahead of its return this October to Dublin's Gaiety Theatre, Tanya Dean joined director Vicky Featherstone and actor Stephen Rea at rehearsals, to discuss their work together on their acclaimed revival of Samuel Beckett's masterpiece Krapp's Last Tape.

Tanya: I know you two have worked together before on David Ireland’s play, Cyprus Avenue, in the 2016 Abbey Theatre/Royal Court co-production. Did that experience influence the decision to work together again on this?

Stephen: It's always good to work with somebody that you like and trust and admire, and someone who you think will understand the material. So it was a very simple choice.

Vicky: I was introduced to Stephen in Cyprus Avenue, and it's been one of the great honours and privileges of my life to meet him and to work with him, to get to know him, and for him to become part of my family and my world. We do create communities to make theatre; we come together because we believe in our shared humanity. I do think that’s how you make your best work. And we talked about doing Krapp’s Last Tape, because Stephen had said that he wanted to do that play at some point far in the future.

Stephen: Roughly 12 years ago, I did record the early tapes. With Beckett, there's always a relationship between all the things, and when I'd seen the play before, I was never quite convinced by the early tapes; I thought it was a bit frozen. So I recorded it.

Vicky: It's extraordinary, because the play is in three parts, really: the setting up, the listening, and then the speaking. And I was watching Stephen as Krapp listening to the tape, listening to himself, and I was thinking that this is the older person genuinely listening to the younger person. The authenticity of that is heart-breaking. That is what Beckett wrote, and Stephen has created it.

and he didn't like Waiting for Godot."

Stephen: It is like when you when you watch a film that you've been in; after a while, it stops being you. You watch it differently.

Tanya: The tape that Krapp is listening to gets filed in the ledger under "Farewell to Love"; what do you think is the relationship that Krapp has to love?

Vicky: I think that he's a fool for love and he falls very quickly; something that recurs all the way through the play is how he falls into people's eyes and that shifts him in some way and he seeks that out. And of course, he has his big epiphany—which is the same as Beckett had—standing in the wild storm and thinking about the work that he should make; and he can't, because love has stopped him from being able to. So love is the most important thing in his life, and the thing that he has to get out of his life in order to be able to continue to create. But then he can't create, so he's lost everything. So I think Krapp is deeply, deeply romantic.

I asked him the meaning of a particular line. He said, "don't think about meaning, think about rhythm."

And he is trying to remember what this tape is in order to get back to that feeling, which I feel was the purest moment that he had. He ended it and he's had to live with the emptiness ever since. And he's realising, I think, in this last day or night, that literally nothing has happened that's been worthwhile in his life since that moment. It’s desperate. What Krapp does—which is something that we recognise in other people—is he sabotages his own happiness because he can't handle the weight of it.

Tanya: And of course there is also a deliciously sly humour to Beckett: "Krapp’s Last Tape" and a literal banana peel moment. How are you finding working with the comedic aspects?

Vicky: I think Stephen—which is why he's so perfect for this part—naturally holds melancholy and darkness, and a childlike sort of humour, both in the same beat. And that is definitely what Beckett was playing with.

And I think as well that the comedy at the beginning (with the banana skin and all the repetitions) is so that we can't sentimentalise the fact that this man is old and that it's his last tape. Beckett throws us into something else; we don't start it with sadness. He decentralises it every time. That has to be left until it's time for us to think of that. It’s so clever.

Tanya: Stephen, you of course actually worked with Beckett at the Royal Court; how did that come about?

Stephen: Well, it all goes back to Jack McGowran. Jack gave me my first job in London, in Shadow of a Gunman. I'm always shocked when young Irish actors don't know who Jack was and who don't know who Marie Kean was; they might have heard of Patrick Magee. But to me, to me those people were always part of my heritage because they transformed Irish character acting.

In 1976, they were going to do Endgame at the Royal Court for Beckett’s 70th birthday, and Jack [who had famously played Clov in the 1957 production at the Royal Court] had died. So the Royal Court phoned me up and asked me to meet with the director, Donald McWhinnie, because Donald had said, "well, you need an Irish actor who can be funny." And so I met with Donald and he said, "would you play Clov?"

Jack's widow, Gloria sent a message to me saying Jack would be proud. And Tara, his daughter eventually gave me Jack's copy of Shadow of a Gunman. And so I'm very connected to Jack. And I don't say that gives me any right to say that I was as good as him or anything like that. But I absolutely worshipped him.

Donald McWhinnie was a truly great director; so articulate, so well-read. He did the first production of Caretaker by Pinter and he did the London version of Translations by Friel (which I appeared in as well) . Donald directed the production of Endgame and there I was, in the room with the great Beckett (who was at all the rehearsals) and Patrick Magee. So Magee and Beckett and McWhinnie and this little whippersnapper. It was a heavy learning experience, because Endgame is a tough thing. I remember Beckett saying he loved Endgame, and he didn't like Waiting for Godot. And I said, "well, it's been absorbed". And he said, that's it, he said, it has been absorbed.

So it was an extraordinary learning experience for me. I was climbing a mountain to get at the level of these three men. When Magee was on form, it was certainly the best performance I've ever been on a stage with; it was absolutely incredible and inventive beyond belief. It's the movement away from the whole notion of naturalism.

Tanya: I remember reading in an interview that you said that Beckett gave you a couple of notes that you found transformational for the possibilities of what modern acting could be.

Stephen: I asked him the meaning of a particular line. He said, "don't think about meaning, think about rhythm."

The other one was a beautiful note: Clov says "I’ll leave you", and he repeats it. And I said, "at this point, Sam, is he leaving to go to the kitchen or is he leaving for good?" And Sam said, "it is always ambiguous". And that is a great note for acting that isn't based on "intention". Because people do spend their lives not knowing what they're going to do.

having the writer in the room." (Pic: Jill Mead)

Tanya: Stephen, you of course actually worked with Beckett at the Royal Court; how did that come about?

Stephen: Well, it all goes back to Jack McGowran. Jack gave me my first job in London, in Shadow of a Gunman. I'm always shocked when young Irish actors don't know who Jack was and who don't know who Marie Kean was; they might have heard of Patrick Magee. But to me, to me those people were always part of my heritage because they transformed Irish character acting.

In 1976, they were going to do Endgame at the Royal Court for Beckett's 70th birthday, and Jack [who had famously played Clov in the 1957 production at the Royal Court] had died. So the Royal Court phoned me up and asked me to meet with the director, Donald McWhinnie, because Donald had said, "well, you need an Irish actor who can be funny." And so I met with Donald and he said, "would you play Clov?"

Jack's widow, Gloria sent a message to me saying Jack would be proud. And Tara, his daughter eventually gave me Jack's copy of Shadow of a Gunman. And so I'm very connected to Jack. And I don't say that gives me any right to say that I was as good as him or anything like that. But I absolutely worshipped him.

Donald McWhinnie was a truly great director; so articulate, so well-read. He did the first production of Caretaker by Pinter and he did the London version of Translations by Friel (which I appeared in as well) . Donald directed the production of Endgame and there I was, in the room with the great Beckett (who was at all the rehearsals) and Patrick Magee. So Magee and Beckett and McWhinnie and this little whippersnapper. It was a heavy learning experience, because Endgame is a tough thing. I remember Beckett saying he loved Endgame, and he didn't like Waiting for Godot. And I said, "well, it's been absorbed". And he said, that's it, he said, it has been absorbed.

So it was an extraordinary learning experience for me. I was climbing a mountain to get at the level of these three men. When Magee was on form, it was certainly the best performance I've ever been on a stage with; it was absolutely incredible and inventive beyond belief. It's the movement away from the whole notion of naturalism.

and admire, and someone who you think will understand the material."

Tanya: I remember reading in an interview that you said that Beckett gave you a couple of notes that you found transformational for the possibilities of what modern acting could be.

Stephen: I asked him the meaning of a particular line. He said, "don't think about meaning, think about rhythm."

The other one was a beautiful note: Clov says "I’ll leave you", and he repeats it. And I said, "at this point, Sam, is he leaving to go to the kitchen or is he leaving for good?" And Sam said, "it is always ambiguous". And that is a great note for acting that isn't based on "intention". Because people do spend their lives not knowing what they're going to do.

Vicky: It's the first time I've done a play for maybe 25 years without having the writer in the room. I know so much has been written about Beckett, but I've really approached this like as if it’s a new play. What's so exciting is being able to have the direct conversation with Beckett through Stephen in a way. And Beckett’s understanding of the whole of theatre is so shocking, when you just look at how he's refined his work and the purity of it.

Stephen: Most people's understanding of theatre is to be very versed in it and to repeat what other people have done. Whereas he saw it as a particular thing: part of it was music hall, and poetry, and music, very much music.

Vicky: He's so amazing with language and with rhythm, but he really looks at that in a three-dimensional setting and a lot of writers—a lot of brilliant writers—don't do that. They leave that for the people who will interpret the world. He immediately puts it into something; his writing of it is three-dimensional, which is kind of mind-blowing. The thing I think that we're really observing in our rehearsals is how vital the rhythm of the physical stuff is, as well as the language, and how the rhythm affects the audience.

Stephen: And also, we are becoming part of the tradition of doing it. Those actors, they changed things. In a strange way, sometimes it takes a long time for a play to become available to everybody. But eventually, through many performers, it becomes more available.

Vicky: And it really does feel like we're all looking at a new play that hasn't been done before. We not bringing a weight of pain or history to it, and that feels really exciting.

Krapp's Last Tape is at the Gaiety Theatre, Dublin from October 21st - 26th - find out more here.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.