Head of the IFI Irish Film Archive Kasandra O'Connell explores the IFI's ongoing mission to preserve and restore a number of Irish screen classics...

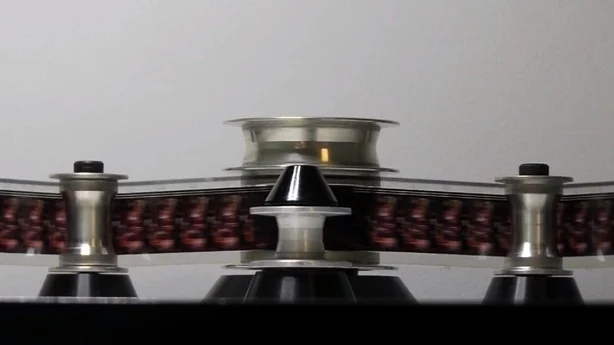

Film is a fragile thing, every time it runs through a projector its surface emulsion is damaged, leading to degradation over time.

Making new prints on film stock is an expensive and time-consuming process and making them available to audiences necessitates people gathering in site-specific locations where film projectors are still maintained and staff with specialist training are employed.

While nothing compares to the communal experience of seeing a film print screened in a darkened theatre with other people, the development of digital technologies has allowed film archives to make their collections available in many other ways. While I've previously talked about how this can create an unrealistic expectation that everything in an archive can be made available, one of the other impacts of digitization and mass accessibility is the transfer of archival language into everyday use - often without a real understanding of either the terminology or technology.

Over the last 20 years, I've observed the words digitization and restoration being used interchangeably by the general public. Many people equate the process of digitisation with making a film look better, when in reality it is just the transfer of the visual content from one form to another.

As the quality of recent digital copies is often vastly superior to the pre-existing copies of archival films, people tend to equate the process of digitization with the superior picture quality. It’s similar to the misconception many people have about the speed of silent films, thinking the accelerated movement is how these films are meant to look, not realizing that this is actually a result of modern equipment not being able to transfer the footage at the correct frame rate, which would have resulted in more realistic movement. Due to the ubiquity of poor transfers at an incorrect frame rate, audiences often think this is how the film was intended to look. It’s a similar case with picture quality, we are so accustomed to standard definition transfers that have lost much of the depth, texture and contrast of the original film that seeing a clear scan of the material is a revelation.

Digital technology now allows us to produce High Definition copies of archival films that retain their visual quality and produce realistic movement. This understandably leads many people to (mistakenly) believe that the digital copies have been restored, given their superiority to older standard definition transfers. We found this to be the case with the Irish newsreels project, where the public were familiar with much of the 100 year old footage already, but in a lower resolution format. The beautiful digital copies we created from the original nitrate prints astonished people who assumed significant restoration work must have taken place. This wasn’t the case, we had just captured all the beauty and detail of the original prints.

Perhaps as a result of this misunderstanding the words digitization (to make a digital copy of something) and restoration (to bring something back to its original form) have become synonymous to the general public. To archivists, a restoration is a very specific thing. The International Federation of Film Archives says "When restoring materials, archives will endeavour only to complete what is incomplete and to remove the accretions of time, wear, and misinformation. They will not seek to change or distort the nature of the original materials or the intentions of their creators". For example, projects like Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old (2018), created from colourised material preserved by the Imperial War Museum, is not a restoration. Despite being referred to as such by Jackson and many of those reviewing the project, the liberties taken with the archival footage makes it a new creative work rather than a restored one.

The IFI Irish Film Archive is undertaking a programme of true restorations thanks to dedicated funding from Screen Ireland. This has allowed us to revisit older films in our collection such as The Outcasts (1982), Reefer and the Model (1987) and Helen (2008). All three have screened in the cinema following a lengthy process to assess and digitise multiple prints, piece together the best sound and picture elements and employ sophisticated tools to remove dirt and damage, before finally re-grading the picture in consultation with the filmmakers themselves. This work is time-consuming and resource heavy, therefore not feasible for all films, nor indeed necessary. Some film prints held in our vaults are in excellent condition as they were acquired solely for preservation purposes and have never been screened. In cases like this we are able to remaster rather than restore. A process of digitisation, tone, colour and contrast adjustment results in an excellent digital copy without a lengthy restoration process. Remastering rather than restoring titles allows us to create exhibition quality digital copies more quickly and inexpensively, which allows us to make more material available to audiences.

However, it’s worth keeping in mind how much time and skill restorations require and pausing next time you feel yourself using the terms digitisation and restoration interchangeably. The Screen Ireland digitisation project aims to create 25 digital exhibition copies of older Irish films over a 5-year period: Reefer and the Model can be seen here, Helen can be seen here and The Outcasts will be available on Blu-ray later this year.

Find out more about the IFI Irish Film Archive here.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.