Aidan Kelly Murphy introduces photographer Shane Lynam's new exhibition Pebbledash Wonderland (2014 –2024), a unique photographic account of his adopted home city, Dublin, and its changing urban landscape, currently showing at Photo Museum Ireland.

For the last few years, myself and Shane have caught up every few months to discuss his ongoing project: Pebbledash Wonderland. Ostensibly this was to look at the latest images, but invariably the discussion would shift to conversations about Dublin, its history, urban spaces and their materiality and our own experiences of living in a city we're not from. As the project drew to a close, and ahead of its exhibition at Photo Museum Ireland in 2024, I returned to the notes that we’d shared prior to these meetings to write a text that layered in those anecdotes and conversations. Over the years, a series of voice memos and phone notes had built up from when I was moving through the city and contemplating the project. The resulting text should be thought of as a walk through the city, through themes of memory, time, materials, and imagery. It serves as one half of a conversation that I feel is completed by the images in Pebbledash Wonderland.

I can’t recall what started the handball craze that gripped my peers in 1999. With the adults focused on much larger and existential affairs, such as the soon-to-be-debunked Y2K panic and a changing Ireland, we were obsessed with smacking a ball against a wall – and any wall seemed to do. The apathy towards wall specifics was contrasted starkly with the clear hierarchy of ball preferences, with that little blue GAA ball reigning supreme. Gorey’s handball alley had fallen into disuse many years before – eventually being demolished to create a car park – and was instead a location to mitch, smoke cigarettes, or sneak off for a shift, with teenagers frequently looking to combine as many of the three as possible. Robbed of an official venue, unofficial venues dominated. In school, the giant outer wall of the gym served us well, whilst at home we made use of a wall tucked away at the back of the house. It was perfect, almost perfect. A windowless surface and a half story high, it was away from the main thoroughfares of the kitchen and living room with a concrete surface in front that facilitated bare-footed games. As I said it was perfect, almost perfect; the one issue? The pebbledash.

Each home game between myself and my brother always started with the best of intentions: take it handy, practise your shots, but don’t go too hard. Invariably we’d fail at this and dislodge stones, remembering to discard them into the shrubs behind us when the game ended.

After a sustained period of intensity, the handball craze ended almost as quickly as it emerged – though the damage to the wall remains visible more than two decades later. On a recent visit I scanned the surface; the tiny craters missing their stones, indicating the hours spent hurling a ball towards it and the stones off of it. I grew up in that pebbledashed home in rural Wexford, and now I live in a pebbledashed home in inner city Dublin – two buildings clad with stone by someone else. The time that spanned these two buildings – the Tiger, the boom and its bust, the emigration of familiar faces, the birth of children – all condenses into one patchwork of memories. The scree of stones that sit amongst the shrubs of my parents’ garden remind me of Shane Lynam’s photographs in Pebbledash Wonderland. They sit together in a collection of recollections, removed from their context and their retaining wall, signifying both their relation to now and the passing of time since they were dislodged – we are as young as we’ll ever be, and as old as we’ve ever been. Pebbledash Wonderland is a measurement of space and events, as well as our relationship to them, and our placement of them in time, reminding us that any description of Dublin should contain all of its past.

One of the earliest, and most formative, visual cataloguing of Dublin that I experienced came from a set of placemats. Growing up, dinner was at 6pm daily; and as we awaited it, and the Six One News, we had our placemats for visual company. There were two sets, the first being a series of mid-18th

Century British landscapes that took up the whole cork-backed board, the second was the set of Malton’s Views, framed with a gold band and set against a forest green background. I appreciated Gainsborough and his contemporaries, but they felt too speculative and distant. Whereas their views had long been lost to industrialisation, Malton’s remained. They formed a cohesive, if somewhat ambitious and romantic, view of Dublin; their lost Georgian context providing ample fodder for exploration, with the changes to these buildings, their surroundings, and their relationship with the city only adding to their allure. As a child Dublin existed in many different forms, it was this 1,000-year-old-city, it was where we went for trips such as the Zoo or football matches in Lansdowne Road. It was where we went for Christmas shopping in town and where my grandparents lived – it inhabited my head as several distinct places, rather than as a single unified space. The journey there was marked by the towns and pubs we passed on the way: Arklow, The Beehive, Jack Whites, and Ashford. Just as important as these main signifiers, were the smaller signals, like the Wimpy Burger at the service station in Rathnew. Dublin was as much a visual journey as it was a destination, with these signs a shorthand for how long we’d travelled and how much longer we’d had to go. They didn’t relate to a place, but rather a place in time. In Pebbledash Wonderland, these visual journeys are through Dublin’s streets and laneways as they, and it, are deconstructed – each image orbiting the wider concept of the city – with us the viewer piecing together our own views as we pierce our way through our own memories.

Many have contributed to the visual history of the space, in terms of both physically representing it, and in articulating the sensation of moving through and viewing its space and inhabitants. From historical views, such as those from Malton and the Roque Map, to contemporaries such as photo books by Evelyn Hoffer and Krass Clement; we even have those who walked the city and documented their own perspectives such as Alderman Kelly’s The Street of Dublin. Dublin exists as many things, with them all layering together to form its spatial history. It is even represented as a literary device; with one of the most famous novels of the 20th century, Ulysses, being a day walking and travelling through the city. Having left Dublin in 1904, and last visiting in 1912, Joyce’s Dublin was drawn from his memories of the city. It was contemporary but already historical – there are real people and real places in his narrative; and in the century since an entire economy has arisen from that blend of fiction and reality. All desire is memory, and these memories are very desirable. Living within that device, and seeing it, reminds you that Dublin is a multitude of things to a wide array of people. And, whilst Joyce’s layered history is presented in a single day, Lynam layers his single city in a multitude of histories and moments that exist all at once but never at the same time.

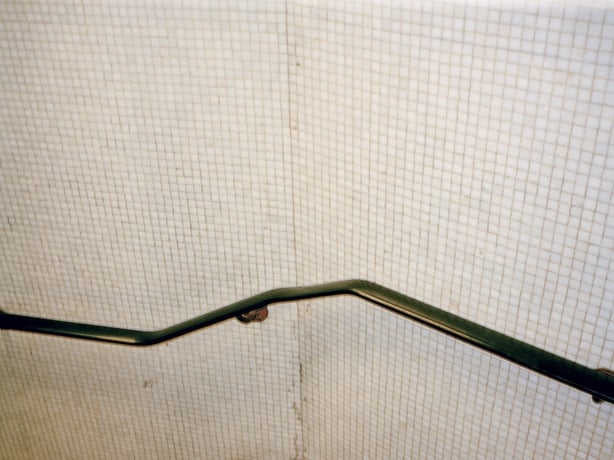

The materials and architectural styles in Dublin point to these overlapping and intertwining histories. Georgian Dublin refers to both a time, 1714 to 1830, and the architectural style that still survives in the city to this day in the buildings and streets constructed during this timeframe. It exists as both a time and a space, a dual existence as a historical and contemporary entity. Buildings often show us their age, and then they age us as we try to make them anew – highlighting the predominant and passing tastes of the period when their changes are enacted. Cities and urban spaces could often be identified and located, both geographically and in time, by the materials they were built out of. Paris is one of the most famous examples of this. The city is built from Lutetian limestone – more commonly known as 'Paris stone’ – which comes to dominate its aesthetic and experience. Baron Hausmann’s clearing of the numerous streets does as well, removing many mediaeval elements and views. Dublin too has experienced street widening processes, from the Wide Streets Commission in the middle of the 18th Century, through to the ill-fated process of adjusting streets in the second half of the 20th Century to facilitate cars. Fortunately not all of Dublin suffered the fate of places like Bridgefoot and Clanbrassil Street – though that doesn’t lessen the impact felt by residents of those areas – and we are left with a unique warren of lanes and winding streets which helps to signify the passing of time in Dublin. We see a unique assemblage of tastes with the overlapping and enveloping styles of neighbourhoods creating an unstructured environment that holds itself together. We see quirks of layouts created not always through deliberate design but by the expanding need. The concept of the city as a canvas, and one that will never be truly finished, comes to the fore in Pebbledash Wonderland. The layers of paint, the contemporary additions to architecture, in particular the materials opted for, give us clues that we fill out based on our own personal interpolations of the images. The colours, the planting of Cabbage palms, the choice of different types of pebbledash, they reference a common visual language that is made up of different accents. These all contribute to give Dublin, and Lynam’s images, a distinct cadence that you experience as you traverse them.

I have never owned a car in Dublin, so my movement around the city and my perspective of it has been shaped by the public transport near me and by walking. My first two years in the city saw the coastal trip on the Dart from Dun Laoghaire, whilst over a decade working in Sandyford means that the turn before Harcourt on the Luas is guaranteed to wake me up from any slumber. Ultimately on foot remains my favourite choice, and every few summers I find myself walking through Dublin with an old friend who had grown up in the city but no longer lives here. We met in college in the early 2000s, spending our twenties working and socialising in the city, criss-crossing its streets in search of people, photographs, and pubs. More time has now elapsed since they emigrated to Canada than we spent in Dublin, leaving the city just before my first child was born – a moment that made my wife and I realise that we would be staying and not returning to our respective counties. Growing up on Clanbrassil Street, invariably our walks would either start or finish in The Liberties, walking the city on the dual hunt for changes and familiar haunts. We walk through Dublin to find the Dublin we remembered but also the Dublin that is changing; the views that are evolving, cataloguing the memories we have of the city as we go. The changes I experience in a slow and ongoing process become instant wholesale changes for them like the ageing of my children. Frequently it's the visual overload first, a new building, or an addition to an old. Like many cities, Dublin’s history is one that is also about what is missing, lost, or removed just as much as it is about what remains – and the longer you spend in it, the more you are acutely aware of this.

I have now lived in Dublin longer than Wexford. I wondered whether the feeling of transition would change, and whilst no longer an outsider, I don’t quite get the sense of being an insider – a feeling I heavily attribute to why I spend so much time walking through and around the city in an attempt to understand it more. Dublin feels like one big brain, a large cauldron of memories. Its main roads and rivers, those core and formative memories. Over time, certain elements get lost, like the rivers buried under pavements or merged together like mediaeval lanes. Often we avoid those squirrelled away moments and memories, as they are or can lead to negative outcomes – like recalling an adventure through the city with a friend, only to remember they’re no longer there. Lynam images and walks aren’t necessarily always happy memories being walked down – but there lies the central paradox of the city, of any city, of any space. Those moments can lead to incandescent memories; rich, vibrant, and bursting forth with emotion. These are most apparent in This is it, this be all, a reflection on a time when movement around the city was restricted, and our experience with it and its inhabitants shifted dramatically. Here we are reminded that periods of stress can result in monuments. We see contracted movement that results in an inward perspective, and are reminded that the temporality of certain monuments can be measured against a time scale that is comparable to a human lifespan. Some monuments even generate a spectacle in their destruction, leaving a lasting oral testament to their past existence and the memory of their end, like Nelson’s pillar becoming the Anna Livia (aka the "Floozie in the Jacuzzi") before becoming The Spire. In this sense, Pebbledash Wonderland acts as a mnemonic to the city it captures, creating a visual legacy that will remain long after its creation.

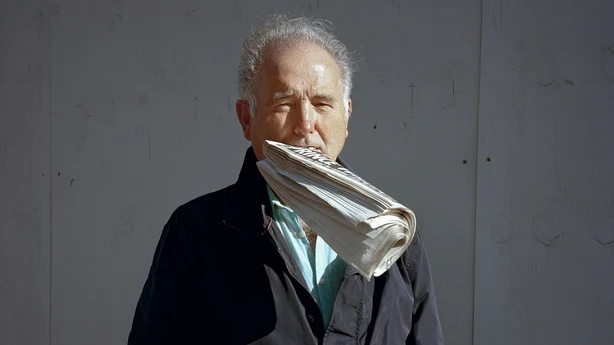

When I walk through Dublin I walk on paths familiar, walking through memories, journeys that I have taken many times. I gave up trying to feel ‘lost’ in Dublin several years ago – the real lost where you can’t tell if the Liffey, the Dodder, or the Tolka are north or south of you. Instead, I’ll attempt to find a new route, purposely deviating down streets and lanes as I move through the city in search of a version that I have never been down before. I look for signals that I am both lost and familiar within the space I inhabit. I search for those invisible cities, those multitudes within a singular space that you can get lost in repeatedly. Lynam’s images speak to this search, reminding you that a familiar path may give rise to unfamiliar thoughts. Pebbledash Wonderland is in conversation with the city it documents, and that conversation talks to moments that are temporal and physical in their experience. This process, this experience of building towards a wider narrative of Dublin, is so personal that it becomes universal in its application. The city can be traced like an expert cartographer inspecting an old map, gauging the creation of your changing borders. You may be presented with the odd clue, a road sign here or shopfront there might give us an exact location, others require no such direct labelling, such as Sandymount strand, with its sandcastles in the foreground ranging us on a time of year, and the ever-changing port skyline in the background giving us some clues on the year taken. We get other clues from within images such as the flora in and out of bloom – buddleia flowers from late Summer to early Autumn, hydrangeas starting earlier in Spring. The presence of people brings a human timescale to the work; and reminds us that the city is both personal and private.

As I walk through town, I lean in closer to the buildings, obscuring the looming towers, cranes, and detritus of a city in flux, a city changing but also continuing, the layers of a space that is over a thousand years old. This closeness to the materials reflects my personal experience of the space. Dublin is Dublin, Dublin is Town with a capital T. Is it a city or is it the City? The answer to this question infers that the idea of what Dublin is has been determined, locked in and written down in order that others may verify and check. One of the central allures to Lynam’s images is not the proposal of multiple Dublins but its demand of them. The work is an ongoing and live archive of the city and its space that is constantly changing, never still – a body of work that is both an archive and a retrospective, a living fossil – we see the photographer as an anthropologist of the city.

Whilst walking through the city earlier this year I came face-to-face with an image from Pebbledash Wonderland. Well, not an image exactly, more the location an image was taken. The building had changed, leaving behind an echo of what was previously captured. Both versions now exist, one in the physical, the other moved to the historical and stored in the memory bank. All memory is nostalgia – and that is frequently sold. Here there is nothing for sale. Instead, we are presented with a living record of being within the idea of a city. All of us, and any of us that want to call Dublin home have inherited the city. But inheritance is not renewal, renewal instead comes from the marks that we leave both physical and personal. I sense that I will, in some part, always carry these images with me on my walks within Dublin, and encounter them frequently, in particular at corners, wondering what wonderland of possibilities lie around the bend.

About The Author: Aidan Kelly Murphy is a writer and photographer living in Dublin. His writing has been published by Paper Visual Art, Visual Artists Ireland, and CIRCA Art Magazine. He is an editor at OVER Journal.

Pebbledash Wonderland (2014 –2024) runs until 12th October 2024 at Photo Museum Ireland.

All pictures via Photo Museum Irelnd and (c) the artist.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.