Sequels to well-known books can be tricky. As we've seen from the way fans have taken ownership over George RR Martin’s A Game of Thrones, or the comparatively lukewarm reception Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light received in the face of earlier successes like Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies, returning to a story after the initial facts have been established is a dangerous game.

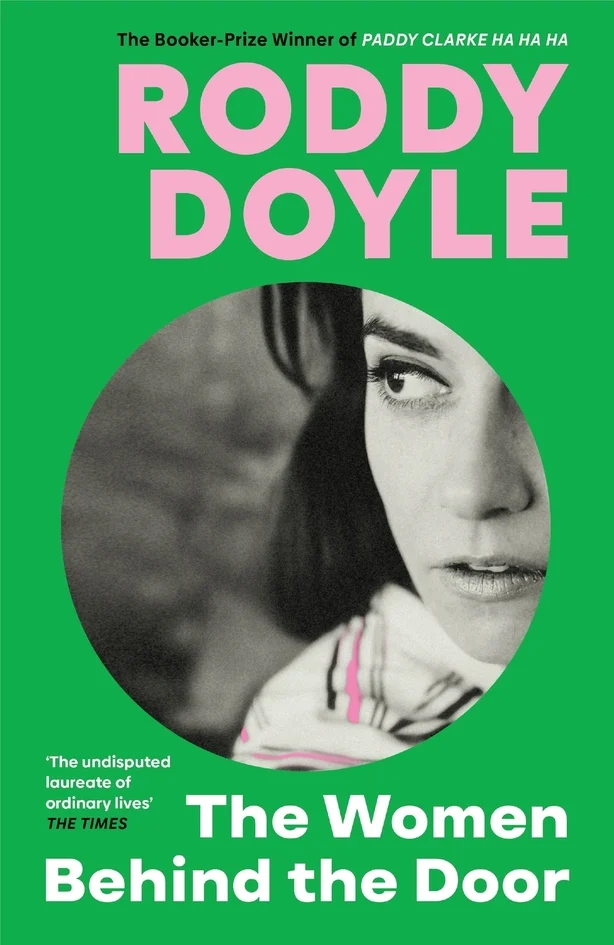

Luckily for Roddy Doyle, he seems to have managed these difficulties well, perhaps even staking his reputation on his ability to navigate them. The Barrytown books that made his early career, as well as The Last Roundup trilogy following the travails of IRA rebel Henry Smart, were all critically and commercially well-received. Now he returns with the third - and possibly final - installment in his Paula Spencer series, The Women Behind the Door.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Listen: Roddy Doyle talks to Oliver Callan about The Women Behind the Door

The difficulty returning to such a well-loved character, however, lies in the fact that when Paula Spencer first appeared in 1996—as the protagonist of the harrowing The Woman Who Walked into Doors - she became a national symbol for the ill-treatment of women in Irish society. A cause celebre in the immediate aftermath of the 1995 Divorce Referendum, when women who were facing domestic abuse did not have the option of legally dissolving toxic marriages to violent partners.

Now we’re in a different Ireland—if only nominally—where the Paula Spencer who survived her turbulent marriage to the sly, criminal Charlo has aged into what she calls ‘semi-retirement’. Now in her sixties, we first encounter Paula on the eve of her booster vaccination for COVID-19; an independent woman with battle scars and grown-up children, living on her own in the house she spent so long fighting to retain.

Ultimately then, this is a novel about mothers and daughters.

In this, Doyle sets out his statement of intent early on: "[Paula] expects everything she has to break. Everything in the house that has a switch or a button. Every friendship, every relationship. Her family."

What Doyle does so well—and why following up with the character of Paula Spencer for the second time feels so important—is tracking the afterlife of abuse; the ways in which trauma can mark even stable periods in a person’s life with lasting consequences. We often call people like Paula ‘survivors’ for having borne and ultimately outlasted domestic violence, though what Doyle seems to imply in The Women Behind the Door is that survival is not the be all and end all of toxic relationships. It is a continual project to be worked on and added to; an arduous compendium of trial and error that exhausts as much as it elates, depleting a woman’s energy even if as it’s preferable to the more immediate dangers of abuse and violence at the hands of a partner.

He also explores how the trauma that arises from such a thing can affect future relationships too, especially with children who bore witness to the marriage. In The Women Behind the Door, the relationship at the novel’s centre is between Paula and her middle-aged (‘menopausal’) daughter Nicola; the eldest of her children and, she thinks, the most sensible, who has walked out on her husband after experiencing domestic problems of her own: "Nicola had been Paula’s mother for years, the roles reversed since Nicola was fifteen, younger, since she saw Paula smashing the frying pan down on her father’s head and bullying him out of the house."

Ultimately then, this is a novel about mothers and daughters. About how relationships with our children evolve through the ageing process, and how love shapes itself around circumstances. The reason Paula finds such difficulty engaging with Nicola is because she has never experienced love as a stabilising constant; can only pass it on as a finite resource to be cherished or hoarded. What’s more, since kicking her alcohol addiction to the curb and surviving a lifetime of abuse at the hands of her husband Charlo, Paula is only now coming to terms with the realisation that she never quite learned how to be a mother. That by focusing all her energy on weathering the storm, she is not fully equipped to deal with other people’s problems.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

What makes this so poignant is that while Paula has full awareness of her problems, she lacks the capability to address them. From her perspective, by choosing to stay with Charlo for as long as she did, she exposed her children to abnormal family dynamics. She therefore feels responsibility for Nicola’s predicament with her own husband and knows that learned behaviour as a response to trauma can be passed down through the generations, just as surely as physical features like eye colour or skin tone. "Guilt. That was what Charlo had left her. The family jewellery. A necklace, pearls of jet-black guilt."

Paula’s self-awareness is what drives The Women Behind the Door as a worthy sequel. Doyle understands that part of the reason domestic abuse relationships proliferate - part of the reason they’re so common - is because violence and affection often intertwine within the same language. In these instances, the thing that is craved for is withheld and controlled while the thing that annihilates looms closely in the background; interchangeable, unpredictable. Abusers evoke the possibility of one to offset the seriousness of the other and invoke affection in times of crisis as a controlling tactic. This is why so many victims stay in long-term abusive scenarios. Fear is only part of the thing which is preyed on. The other part is love. "Charlo was the father of her children. He’d been in love with Paula. He’d kissed the ankle she’d just been examining. It was one of the bones he’d never broken."

The Women Behind the Door is published by Jonathan Cape

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.