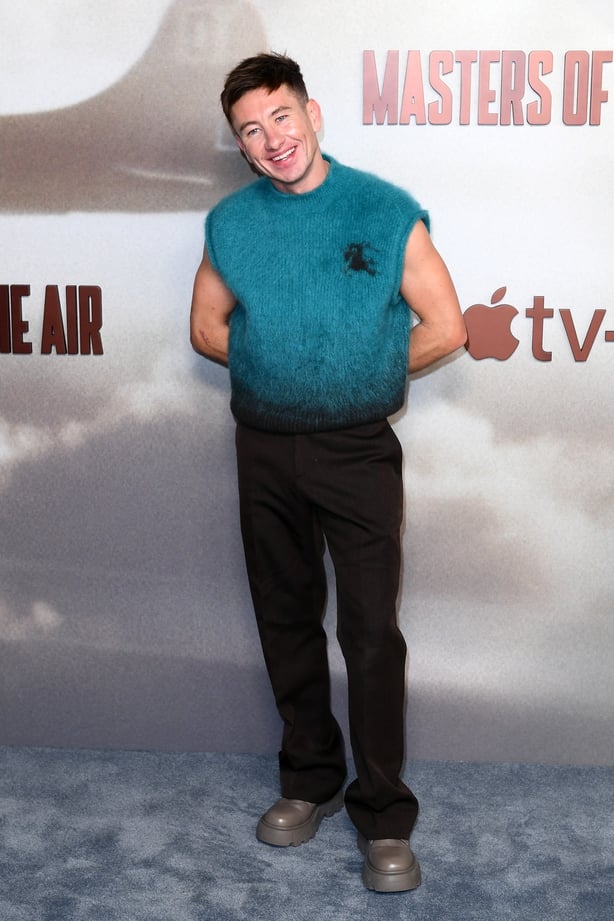

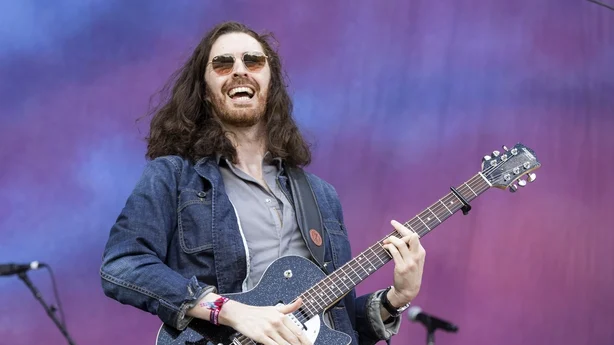

In 2024, Hozier became the first Irish artist in 34 years to top US charts; Cillian Murphy became the first Irish-born star to win Best Actor at the Oscars; Barry Keoghan set the internet ablaze with his memorable moves in Saltburn. So, why are Irish men so popular right now? Kate Demolder writes.

'They're both so baby girl,’ the caption on a TikTok video of Paul Mescal and Andrew Scott nearing 200,000 likes reads.

The 23-second clip features both men on the All Of Us Strangers press tour, wherein they dissect the modern cultural lexicon of Generation Z, such as ‘girl dinner,’ and ‘Roman Empire’.

"Paul Mescal is my Roman Empire," Scott says as his co-star laughs coyly. From six seconds in, the conversation pivots to ‘baby girl,’ a term of endearment popularised by TikTok culture, defined by Rolling Stone as: "A man who is very cutesy in a slightly submissive way".

Candidates include Jacob Elordi, Harry Styles, the South Korean superstar Jimin, and, for the first time ever, Irish men.

We need your consent to load this tiktok contentWe use tiktok to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage PreferencesWe need your consent to load this tiktok contentThe content is loaded from tiktok. We need your permission before loading it as it may use Cookies and other technologiesAllow tiktok Content

Both men laugh at the concept, before Mescal, in a cropped cardigan, relays to Scott that it means 'cute'. Scott replies: "Do you think I’m mommy in real life?"

The term’s usage, and indeed both Mescal and Scott’s gentle appreciation of same, are indicative of the pivot Irish men in the public arena have taken towards the hottest trend of the 21st century––femininity. Some would argue that this is nothing new.

From Bowie to Beckham to Rodman to Cobain, men in the public eye have regularly resisted the trappings of toxic masculinity, opting instead to openly play with gender by way of frothy hemlines or pastel linens. But never before has this sartorial and cultural androgyny felt accessible to Irish men, a breed whose actors were generally relegated to rugged, insensitive, and often boorish roles.

Now that they are––or at least now that Irish men have modern effeminate men to model themselves on––it begs the question for us all: have Irish men embraced femininity? And if so, why has it taken so long?

Irish actors have long made significant contributions to Hollywood, from Maureen O’Hara to Brendan Gleeson to Saoirse Ronan to Cillian Murphy. However, for the longest time, male Irish actors were largely cast in rugged, Martin McDonagh-adjacent roles.

This, perhaps, ties into the anachronistic, US perception of Irish masculinity, perpetuated by the 1845 Famine. At that time, Irish men were seen as uncultured, violent and good for nothing but menial labour. This was reflected in media, where Irish characters could usually be found at the end of a bar or with a gun in hand.

Films like Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), The Informer (1935) and Odd Man Out (1947) feature characters who are dragged into the underworld of the Irish mob in the US, or are dealing with the fight for Irish independence.

This persisted until the introduction of John F. Kennedy, whose Irish links signaled the full assimilation of Irish men in America. Soon after, Irish representation in media pivoted to the twee and nostalgic, acting almost antidotal to the Darwinian commercialisation ravaging the US.

Today, it seems another shift is afoot: that Irish men––with the bashful modesty we're unused to with movie stars, and their tendency towards the mysterious (neither Scott, Mescal nor Murphy have public social media accounts)––are approachable, desirable and sensitive enough to be considered leading men.

Rarely have Irish actors been cast as sensitive, romcom leads––to the point where even Irish roles were given to non-Irish actors (Scottish actor Gerard Butler in PS I Love You, English actor Matthew Goode in Leap Year)––such was their non-romantic nature.

It must be said that despite great strides, drunken, boorish and lazy plot points continued to be pinned to Irish actors right up until the early aughts, like Colin Farrell’s Scrubs cameo character Billy Callahan, who drunkenly fought someone only for them to end up in hospital.

This corrective started, this writer believes, by way of a number of things.

Firstly, and perhaps most dramatically, the global mood changed. When George Floyd died in police custody in 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement was formed, decreeing that no longer would whiteness be shrouded with preferential treatment or untouchability.

People who agreed voted with their feet, no longer attending films that committed to tokenism, or fashion shows that didn't cater to a broader audience. This created a shift in Hollywood, one that benefitted Irish actors in a surprising way.

Though, ethnically, Irish skin has historically been linked with pale skin and red hair, the complex nature of Irish history and identity allowed those with Irish origins to exist within a realm of otherness. The fact that Irish people have a devastating history of oppression seems to have carved out a relatability for the marginalised.

And, indeed, for the movie executive, Irishness presented a safe kind of exoticism, one which was deemed just foreign enough to bankroll a project on.

Secondly, Generation Z have made efforts to disassemble toxic masculinity. By celebrating men who lean into qualities typically associated with women––sensitivity, empathy, care, kindness––those presently younger than 30 years of age caused the hypermasculinity wave that reigned in the early 2020s to fall flat.

In a matter of months, online discourse appeared surrounding the exclusively muscular Love Island frames, and controversial commentators like Andrew Tate fell out of favour.

This was undoubtedly linked to the high tension of the global pandemic, and a number of its byproducts, including the glut of stories about domestic abuse in confined quarters*.

With hypermasculinity no longer being presented as a plus, the desire to be around a man whose greatest strength is his personality grew in popularity. I personally believe this explains the rise of Timothée Chalamet movies.

Closer to home, movements regarding social justice pushed to the fore. Suddenly, men were voting in their droves for women they would never meet, and couples they would never know. Injustices were laid bare and it seemed as if there was a general understanding that retreating to the past would be detrimental to the future shaped the worldview of a whole generation.

They, too, began speaking about their feelings, something that was previously taboo in masculine society, in the hopes of tackling the suicide** pandemic that was claiming their friends.

This paired with staggering rents and a soaring cost of living crisis, allowed many in that generation to turn inward, and seek personhood and creativity rather than capitalistic institutions.

This, in turn, allowed for a generational shift not seen since 1980s punk, where a subculture––in this case, men unshackled by toxic masculinity––grew legs large enough to become normalised.

While this still can't be said for every Irish man, the fact that some of our most popular stars have stepped away from traditional masculine marketing is a comforting, hopeful sign. As such, a welcome positive masculinity is born. (Indeed, as I type this in a Dublin café, two teenage boys with grey tracksuits and pearl necklaces just stepped into frame.)

Enter, Hollywood. A bonafide dream factory intent on giving the people what they want. Which, if any magazine photoshoot with Irish actors of late will tell you, it’s Paul Mescal in thigh-high boots, Barry Keoghan in woman’s tailoring, Cillian Murphy in silk neckties, or indeed any well-known Irish man in the trappings of a 19th-century dandy.

Though these shoots are playful, entertaining and at the very least save us from the boring nature of black-and-white tuxes at every opportunity, the worrying thing about their rise is that their fall is likely imminent.

These things come in waves, as we all know, meaning the end of pearls, crop tops and gender-bending displays on Irish men is likely nigh.

The good thing is, however, that walls have been broken with this new movement, and Irish men––or indeed, any man––can finally feel free enough to explore themselves through art, fashion or laughter-filled conversation about TikTok terminology.

That, I think anyone can agree, is so babygirl.

*If you have been affected by issues raised in this story, please visit: www.rte.ie/helplines.

**If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this article, you can contact; The Samaritans (phone 116123), or Pieta House (1800247247).

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.